Things appear to us by virtue of their subjection to a techne. Unblocking our habitual technological enframings allows us to see things otherwise.

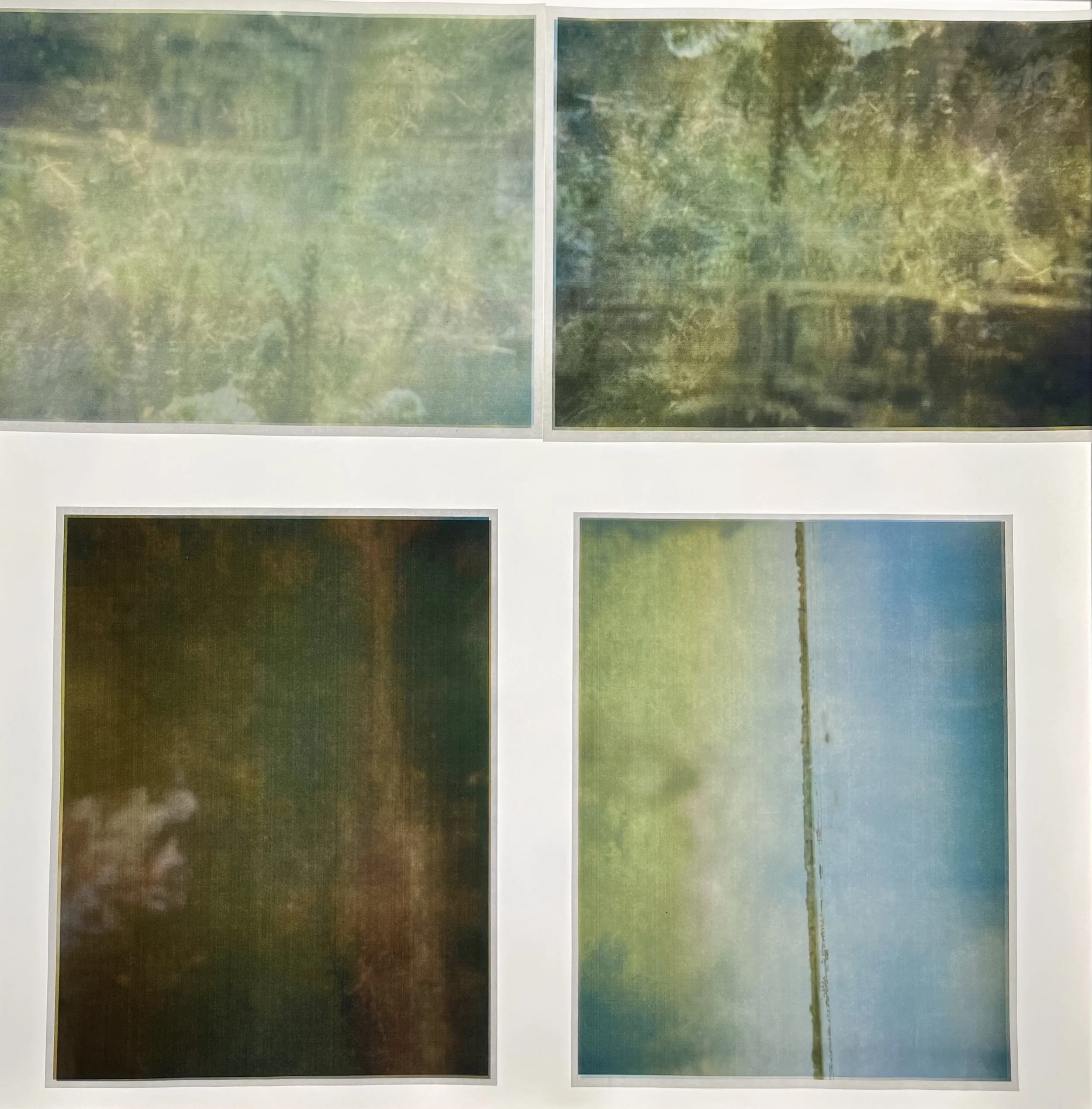

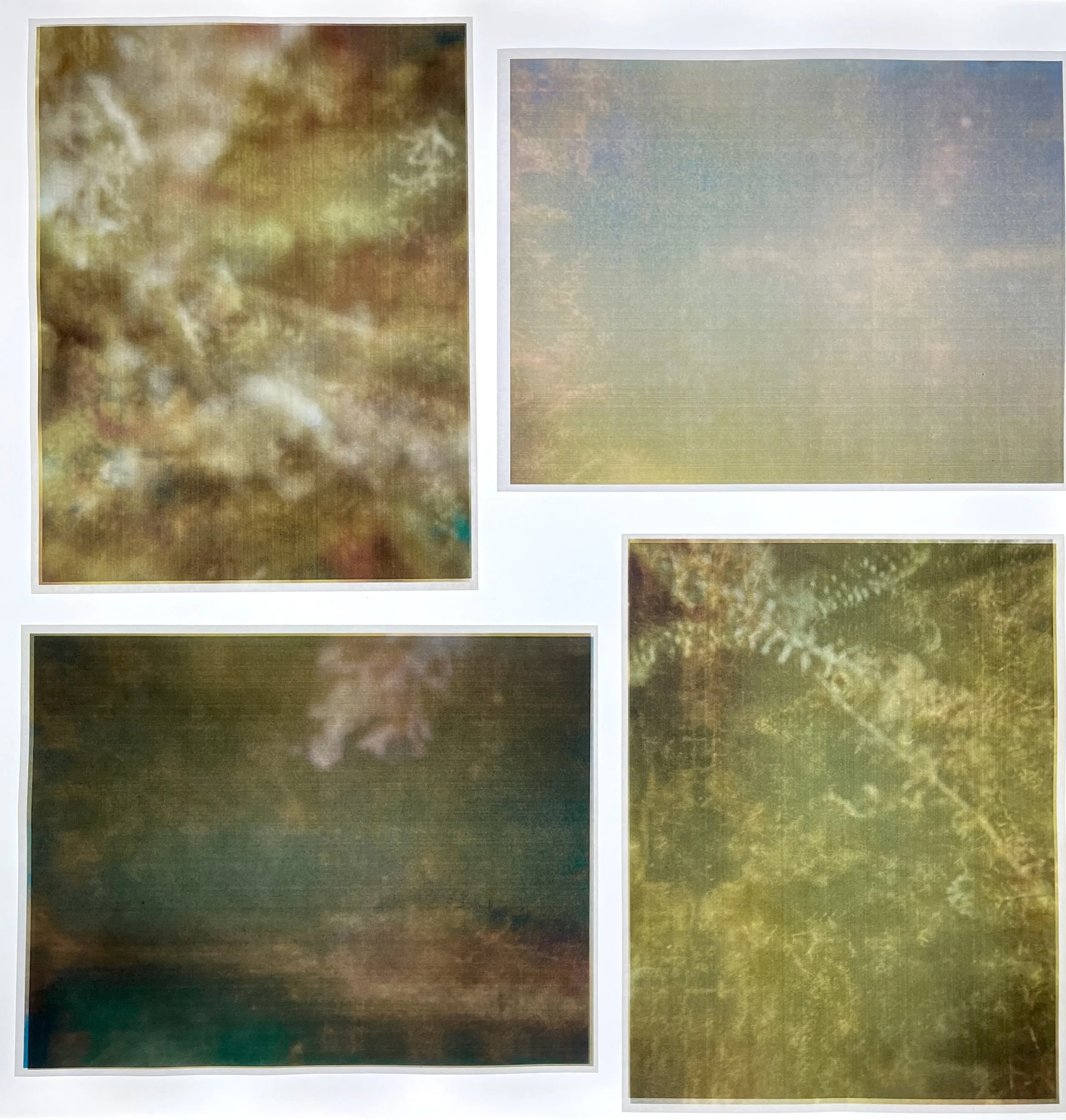

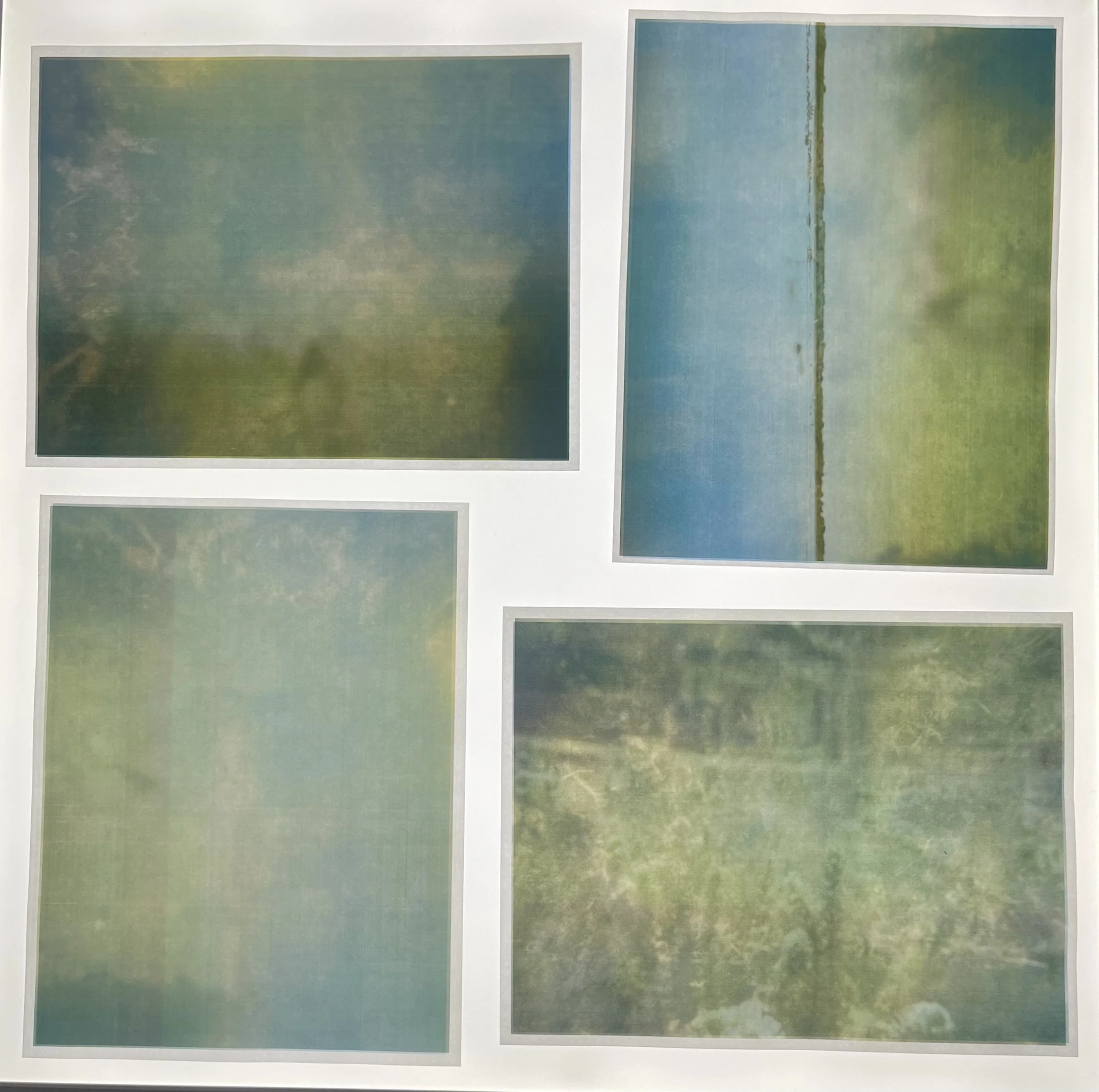

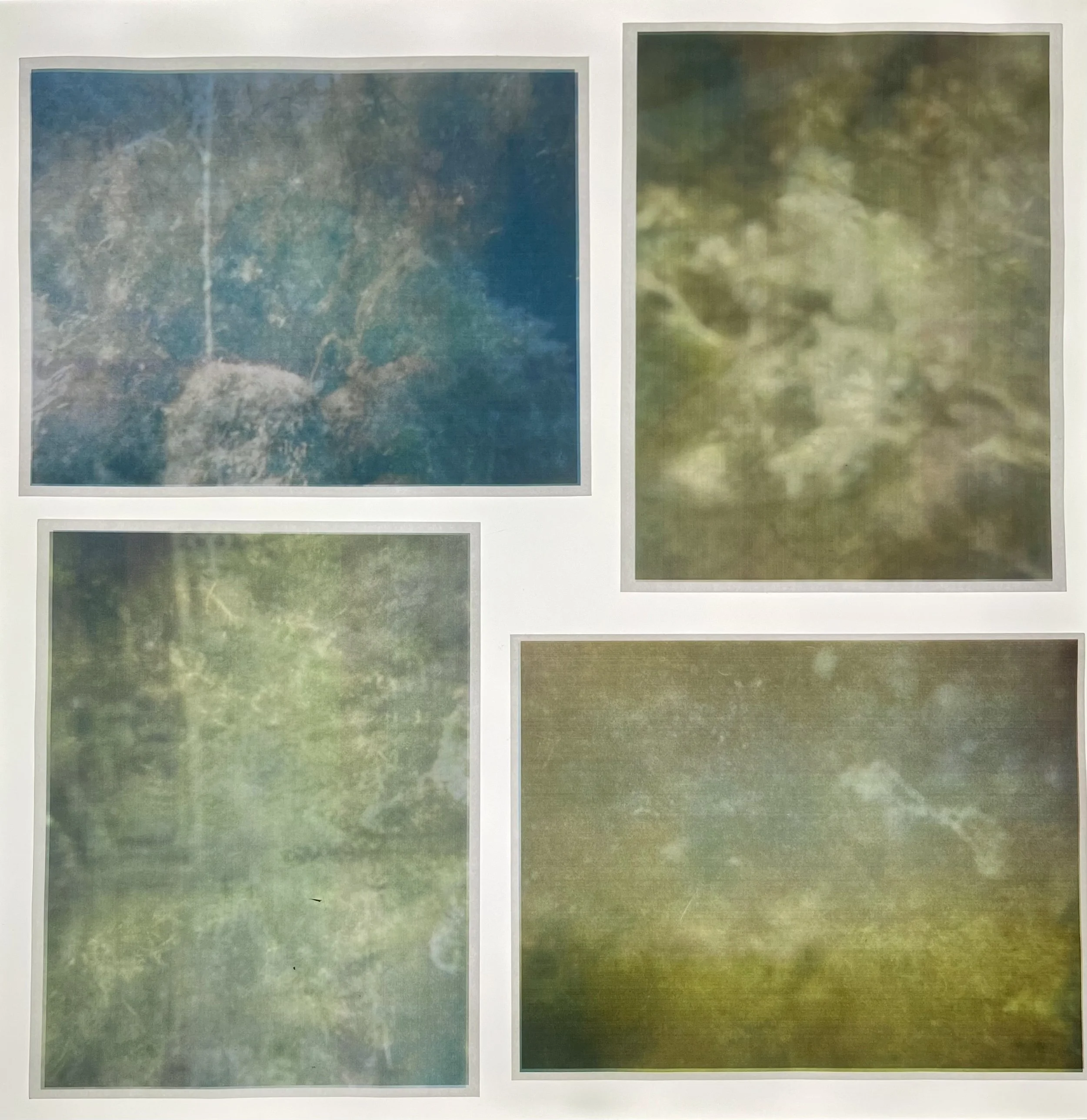

These photographs are an experiment in what happens to landscape photography thrown into a new immersion. The camera used, Nikon’s “Nikonos”, a waterproof 35mm camera, was designed to make cameras immune to environmental media. One of its original ads states its “Designed to function and survive where ordinary cameras can’t go… through the curl of a wave, into a snowbank, even into smoke, dust, and other hostile environments”. Hermetically sealed to the material it clicks through, it gains the ability to see through environmental media, become immune to them, conquer their hostility to the human gaze, attempting to equalize and invisibilize all environmental substrates.

Underwater photography, by means of its subterrestrial locale, doesn’t let you rely on old habits of landscape photography. There’s no horizon. There’s newish gravity. There’s tides in motion. There’s no scale with which you can make sense of your subject. Most times there’s no subject to be found at all, nothing to focus on. It’s hard to parse what kind of light is going on in a river and how to set your aperture. It shifts in relation to your depth and even through different parts of the river– a sunny morning can look like evening in a part of the river that’s thick with algae.

These are things that make it hard to know how to frame a shot, and things that make me aware of how much I rely on these ways of understanding a place. I find myself making unnecessary analogies to air photography. A clot of inch-high aquatic plants can look like a forest. The river floor can look like a hillscape. The river surface can function like a new horizon.

The light cast from above this wrong horizon catches on particulates, making each photo dotted with what looks like sloppy printing. When I first check the negatives I mostly can’t figure out what’s going on. It’s a disordering perspective, it’s unclear where to look, I think it’s a lot like being in the river, getting lost to the liveliness of the volume. Because of this the photos are grainy and abstracted by matter.

Saturation never involves one thing alone, but rather the thick distribution of many co-present elements.

I printed these photos double-sided to double-down on the disorienting effect of encountering the riverscapes. On one side the image is upside-down and that’s just like the feeling of looking during a flip turn. I used a laser printer, whose linear mode of depositing colored ink is laminar like some river flows and adds another material presence. I want to introduce materiality as a rebellion to the Nikonos’ ethos of overpowering it. And so I rubbed these prints in oil which was pretty messy and left a slick all over everything in my room. I did this to make the two sides simultaneously visible when viewed through light. The initial pour of oil creates new patterns of saturation, new liquid tides, and it takes effort to evenly saturate the paper such that the whole landscape is rendered water soaked like I want it. This is an arbitrary precision but accuracy keeps mattering to me, even of abstraction.

A river is too roaming, too mutable and long-traveling, too diffusive to ever encounter as a whole. Long distance runner. Always somewhere else. It resists capture. What would an image of a whole river be? One might have to get a drone or satellite, make a timelapse, or follow each bifurcation and tributary, and later stitch the river together in photoshop. But even these attempts would leave you with something un-riverlike, they’d be just winding lines, hems of fish life, fluky twists, not so much river as string tossed-down into a random curl, fictional curve, blue streak in the earth, absence of land, wet cut. They’d emulate the river’s surface, which is river-like but not river whole.